oekk.oddb.org

Information für Patientinnen und Patienten den, Allergien haben oder andere Arzneimittel Medibudget Lesen Sie diese Packungsbeilage sorgfältig, (auch selbstgekaufte!) einnehmen oder äusser-denn sie enthält wichtige Informationen. Dragées laxatives Dieses Arzneimittel haben Sie entweder persön-lich von Ihrem Arzt oder Ihrer Ärztin verschrie- Dürfen Medibudget Abführdragées B

TABLE 1. Characteristics of mothers and infants

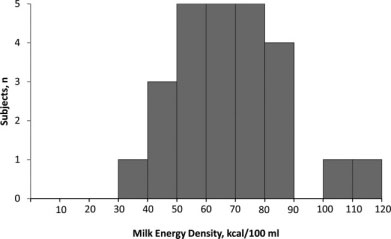

Milk energy density among 25 Massachusetts mothers.

TABLE 1. Characteristics of mothers and infants

Milk energy density among 25 Massachusetts mothers.